The constitutional commitment of

equality, liberty, justice and dignity to all Indian citizens is the expression

of our vision of building a nation without any discrimination including

deep-rooted discrimination based on caste. In the past 68 years of

independence, this commitment made in the Preamble has been translated into

action through various public policies to abolish discrimination. Yet caste

discrimination remains a widespread phenomenon throughout India. The cruelest

outcome of caste discrimination against Dalits and Adivasis is the physical

violence against them by socially advantaged caste groups in India. Recognizing

such crimes and vulnerability of Dalits and Adivasis, the government of India

enacted ‘The Scheduled Castes and

Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act’ in 1989 (PoA Act) to deter

such violence and ensure justice and protection to them. However, its

implementation remains very weak and the vulnerability of SCs and STs has

barely improved. Dalit rights

organizations and various other public institutions indicated towards

non-implementation of the law, in-effectiveness of law to deter commonly

committed caste base atrocities, lack of statutory arrangements in the states,

corruption in police system and influence of caste system in public

institutions. Considering all these loopholes in the Act, it has been demanded

by various stakeholders to amend this law in order to ensure higher protection

of victims and prevent caste-based atrocities. UPA-II government in the end of

its tenure brought an ordinance to amend the PoA Act in March 2014. The newly

formed NDA government introduced ‘The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes

(Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Bill, 2014 in the Lok Sabha to replace the

ordinance.

The Scheduled Castes (Dalits) and

Scheduled Tribes (Adivasis) together accounts around one fourth of Indian

population. Caste system deprives this entire section of population from

enjoying a life as it is articulated in the Preamble of the Indian

Constitution. Practices of the caste system such as untouchability and

discrimination many times lead to the gross physical atrocities. The literature

on atrocities shows that it is an all-India phenomenon legitimized by same

principle of caste hierarchy. Government of India enacted The Untouchability

(Offences) Act in 1955 to abolish practices of untouchability and protect

rights of individual. Even after this legislative mechanism, frequency of

atrocities against Dalits and Adivasis remain unchanged. Under the pressure

from Dalit Members of Parliament (MPs), the Government of India started

monitoring atrocities against SCs from 1974 and in the case of STs from 1981

onwards, with special focus on murder, rape, arson and grievous hurt.

The caste system is so deeply rooted in

Indian society that mere monitoring of atrocities and enacting a law to abolish

untouchability did not result into betterment of Adivasis and Dalits. The

socially and culturally legitimized caste system leads to the complex

manifestations such as discrimination, untouchability, atrocity on vulnerable

sections of the society. The enactment of PoA Act in 1989 as a special law

recognized complexity of caste base atrocities and higher vulnerability of

victims. This special law treats various IPC and other offences against STs and

SCs by any non ST and SC member in a different manner. It prescribes stronger

punishment and provides protection to the victims. The Act states that,

“despite various measures to improve the socio-economic conditions of SCs and

STs, they remain vulnerable. They are denied a number of civil rights; they are

subjected to various offences, indignities, humiliations and harassment. They

have, in several brutal incidents, been deprived of their life and property.

Serious atrocities are committed against them for various historical, social

and economic reasons .”

Implementation

of the Act

During two decades of its implementation

the PoA Act ensured justice, protection and rehabilitation for thousands of victims

of caste atrocities. . It also helped to generate awareness around basic human

rights. Dalits and Adivasis have utilized this law to assert their rights and

due share in society. However, various obstacles have been identified in its

smooth implementation and delivering justice to the victims. According to a

NHRC report on Status of Implementation of SCs and STs (Prevention of

Atrocities) Act, 1989, police resort to various machinations to discourage

SCs/STs from registering cases, to dilute the seriousness of the violence and

to shield the accused persons from arrest and prosecution. FIRs are often

registered under the Protection of Civil Right Act and IPC provision, which

attract lesser punishment than PoA Act provision for the same offence.

The National Coalition for Strengthening

SC & ST Prevention of Atrocity Act (a network of civil society organization

and Dalit activists) identified following major deficiencies of the Act and its

implementation :

·

Under

reporting of the cases under the Act and deterred from making complaints of

atrocities.

·

Deliberately

not registering cases under appropriate sections of the Act.

·

Delay

in filing charge sheet

·

Not

arresting accused and the ones who are arrested are invariably released on

bail.

·

Filing

false and counter cases against Dalit victims by accused.

·

Compensation

prescribed under the Act 16 is invariably not paid.

·

Victims

have no access to legal aid.

·

Non-implementation

of statutory provisions in various States under the Act and Rule, 1995.

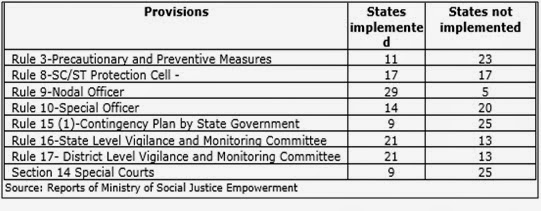

According to the data of Ministry of

Social Justice and Empowerment, majority of states do not fulfill minimum

statutory provisions as per the Act, 1989 and Rules, 1995. Following table

shows the status of non-implementation of the provisions of SCs and STs (PoA) Act,

1989 and Rules 1995 by State Governments.

Although there is provision in the PoA

Act for the constitution of Special Courts to expeditiously try atrocity cases,

in reality what SCs/STs experience is a huge pendency of their cases before the

trial courts. Moreover, the conviction rate is very low. In fact, the

conviction rate under the PoA Act is found to be much lower than in cases

booked under IPC. According to the NCRB data, in 2013 the

average conviction rate for crimes against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled

Tribes stood at 23.8% and 16.4% respectively as compared to overall conviction

rate of 40.2% relating to IPC cases and 90.9% relating to SLL (Special and

Local Law) cases. The processing of reported cases for investigation and trail

is very slow. According to the NCRB

data, 35645 cases are pending in different courts for trial. Large numbers of

cases are pending in States such as Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Odisha, Gujarat and

Karnataka.

The National Advisory Council (NAC)

during UPA government reviewed the provisions of law and cases of atrocities

and found that certain forms of atrocities, though well documented, are not

covered by the Act. NAC recommended for the incorporation of various IPC

offences and other commonly committed offences under the perview of this law to

ensure wider protection to the victims of caste atrocities. The National

Commission for Scheduled Castes (NCSC) and Justice Punnaiah Commission

critically examined deficiencies of the Act and has suggested various

amendments to the Act. Human rights organizations have also highlighted various

gaps in the enforcement of the Act and Rules. Ministry of Social Justice and

Empowerment and Ministry of Home Affairs have issued various advisories to

State governments to fill the gaps in the enforcement.

Status

of Atrocities:

The National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB)

data further exposes the poor implementation of the Act and its minimal impact

in effectively dealing with caste based atrocities. The data reveals that the

number and frequency of crime against SCs and STs are continuously increasing.

The prevalent atrocities against SCs and STs includes incidents such as making

SCs eat human excreta, and subjecting both SCs and STs to physical assaults,

grievous hurt, arson, mass killings and rapes of SC/ST women, etc. Although the

National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) provides useful data that reveal the

extent of atrocities committed against the SCs/STs, these data do not fully

reflect the ground reality as most of the cases go unreported due to reluctance

by police to register atrocity cases for various reasons. One also finds caste

bias and corruption among the police force preventing registration and

investigation of cases.

Even after low rate of reporting of

crime under PoA Act, incidences of crime under this Act has increased from

11602 incidences in 2008 to 13975 incidences in 2013. The incidences of rape

have shockingly increased from 1457 in 2008 to 2073 in 2013 (an increase of

42.27%). There has been no mitigation

with annual average of crimes registered against SCs/ST standing at 39408 and

daily average being 108.

Proposed

Amendments in PoA Act, 1989:

The literature and empirical data on

caste atrocities reveals that it made nominal impact in the lives of SCs and

STs. However, various assessment of the law reveals that it has created a sense

of security and protection among the victims of the caste atrocity. Dalit and

Adivasi victims have used it as a tool to assert their basic rights and combat

with wrong social and cultural practices. The current situation of atrocities and

status of cases pending in police station and in courts led stakeholder to

advocate for amendment in the PoA Act, 1989.

The Scheduled Castes and The Scheduled

Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Bill, 2014 introduced in the Lok

Sabha on July 16, 2014 that replaces ordinance enacted by UPA government in

March 2014 represents the consensus of

stakeholders to amend the law for better results.

The amendment Bill proposes substantial

changes in the chapter on ‘Offences of Atrocities’ (Chapter-II) of the

Principal Act. The proposed amendments attempts to increase number of IPC

offences under the preview of this act. It also recognizes commonly practiced

action in society to insult and harm dignity of person from SC and ST community

as an offence. These offences are

garlanding with footwear, compelling to dispose or carry human or animal

carcasses, manual scavenging, attempting to promote feeling of ill-will against

SCs or STs, imposing or threatening a social or economic boycott. The

amendments in this chapter further specify duties of public servant in detail

and prescribe punishment in case of any neglect of duty by the public servant.

The common duties of public servant includes registration of FIR,

furnishing a copy of information recorded by the informant in police station,

to record statements of victims or witnesses, conduct investigation, file

charge sheet within six days and keep records of document.

Addressing issue of long pendency of

cases and low conviction rate under the Act, the amendment Bill proposes

constitution of Exclusive Special Court and Special Courts to dispose cases

within given time-frame. The provision in the bill ensures adequate number of

courts so that every case can be disposed within the period of two months from

the date of filling of the charge sheet.

The bill has inserted a new chapter namely ‘Chapter IVA’ in the principal Act, that describes the rights of

victims and witnesses in detail. Some of the crucial rights of victims and

witnesses are as follows:

· Right

of victims, their dependents and witnesses to access state’s support for their

protection against any kind of violence, threats, coercion, inducement and intimidation.

· Right

of victims to access special support from government, that arises because of

their age, gender, educational disadvantage and poverty.

· Right

of hearing views of victims at any proceeding under this Act in respect of

bail, discharge, release, parole, conviction or sentence of an accused.

· Right

of victims, their dependents, informants and witnesses to access facilities of

relocation, rehabilitation and maintenance during investigation, inquiry and

trail of the case.

· Right

to access information about trial, enquiry and trial such as recorded FIR and

provision of laws and allied schemes of relief for victims, their relatives.

· Right

to access relief in cash or kind.

· Right

of atrocity victims and their dependents to take assistance from Non-Government

Organizations, social workers and advocates.

Soon after the introduction of the

amendment Bill in the Parliament, the Lok Sabha Speaker referred the Bill to

the Parliamentary standing committee for further deliberation.

Conclusion:

The Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled

Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Amendment Bill, 2014 introduced in budget

session 2014-15 replaces ordinance brought in by UPA-II government in March

2014. The proposed amendments in the principal act comprehensively addresses

issues of non-implementation, in-effectiveness and number of loopholes in the

existing law as highlighted by various human rights organizations, Dalit

activists and public institutions. The amendments in the Act will ensure wider

protection and timely justice to the victims of caste atrocities. It has

already been delayed for so many reasons, but now it is up to the Parliament

and political parties to understand the urgency of the amendment Bill to

provide relief to the SCs and STs who constitute almost one forth of Indian

population.

Jeet

Singh